South Dakota Searchlight

Democracy and discomfort go together. Or at least they should.

A democracy without some discomfort in its educational system and public dialogue probably isn’t much of a democracy at all.

…

This item is available in full to subscribers.

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

Democracy and discomfort go together. Or at least they should.

A democracy without some discomfort in its educational system and public dialogue probably isn’t much of a democracy at all.

So I was feeling democratically (small “d”) inspired and appropriately uncomfortable as I sat at my table at the August Black Hills Forum and Press Club luncheon here in Rapid City and listened to Indigenous social-justice activist and organizer Nick Tilsen talk about Mount Rushmore.

Nobody can make an old white guy feel uncomfortable quite like Tilsen, especially if that old white guy happens to love Mount Rushmore National Memorial, as I do.

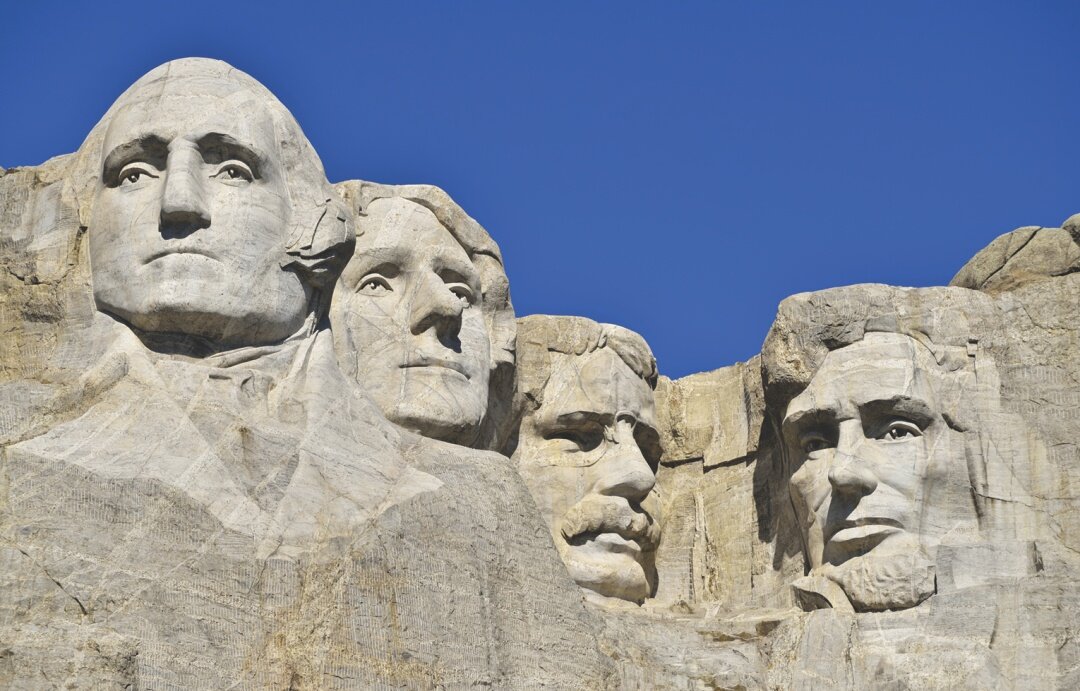

What can I say? I’m a sucker for those massive presidential faces “carved” (as in dynamited and jackhammered) almost a century ago out of the granite face of a mountain.

Of course, I have reservations about doing such a thing to a mountain, which was more elegantly known as Six Grandfathers by Indigenous people — the “six” representing the sacred directions of east, west, north, south, the sky above and the earth below. White folks renamed the mountain after one of their own, of course. Charles E. Rushmore was a New York City lawyer who spent a little time in the Black Hills in the mid-1880s securing mining options.

And for that he got his own mountain, in name at least? Go figure.

A big part of me wishes I could have seen Six Grandfathers before workers started blasting away in 1927. But I’m nonetheless inspired whenever I stop at Mount Rushmore, which I’ve been doing since I first visited the place with my family as a kid. I still feel a bit like a kid when I stand, in childlike wonderment, at one of the viewing areas and gaze up at the mammoth stone faces looming above me.

An amazing piece of art? Absolutely. The Shrine of Democracy? Sure, to many of us, at least.

But it’s something else, too, something even Rushmore lovers like me can’t deny, if we’re being honest: It’s a place of stark contradictions and even hypocrisies. In fact, you could make an argument that the Shrine of Democracy is also the Shrine of Hypocrisy.

Which is pretty much what Tilsen, president and CEO of the nonprofit NDN Collective, did as he spoke at the press club.

“That was a sacred site for our people. That was our church where we went to pray, to give back to our creator,” Tilsen said. “And then it was blown up, and then the faces of the people who are responsible for violating our rights, murdering our people, stealing our children from our homes — those people who created the policy for that to happen, their faces were put on that mountain. You can imagine that disrespect … and then on top of it to celebrate it as a form of democracy is to do no justice to us here.”

Strong words. Words that could make an old white guy, or anyone without an Indigenous perspective, get a bit defensive. Which would be a mistake. Because there are truths in those words, uncomfortable truths that are nonetheless essential to hear and consider and discuss.

The way we should do things in a democracy.

There’s much to admire about the four presidents — Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt — depicted on Mount Rushmore. But two were slave owners and all four played a role in the oppression, or worse, of Indigenous people.

Then there’s the Land Back movement that NDN Collective promotes. Locally it seeks return of the federal land in the Black Hills taken in violation of treaties.

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed, in a 1980 ruling following decades of legal wrangling, that the Black Hills were wrongly taken. In the United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, the high court voted 8-1 to affirm a lower court ruling that gave $17.1 million — the estimated value of Black Hills land when taken by the federal government in 1877 — plus interest over the years of $88 million.

The Sioux Nation never accepted the $105 million, which has now grown with interest to about $2 billion. Instead, Tilsen and many others continue to press for the return of the land, or at least the return of the land owned by the federal government, including Mount Rushmore.

“My opinion is it should be returned to Lakota people,” Tilsen said. “And then we should have decision-making power about what we should do with that place.”

NDN Collective started an online petition with more than 45,000 signatures calling for the closure of Mount Rushmore as well as the return of federal lands in the Black Hills to “the Oceti Sakowin,” or the Great Sioux Nation.

While Tilsen told the press club audience that the land should be returned to Lakota control, he didn’t speak of closing Mount Rushmore or destroying the sculpture. He spoke instead of how Indigenous management of the property would lead to a more complete, more honest story being told at the mountain.

“I think there’s an opportunity to tell the true history of that place, not under the banner of the Department of the Interior,” he said.

The National Park Service, which manages Mount Rushmore National Memorial, is part of the Department of Interior. And especially in recent years, the park service has tried to expand its education-interpretation offerings to better recognize and honor Indigenous people and expand the Rushmore story.

Earl Perez-Foust, program manager of interpretation and education at Mount Rushmore, said in an email that certain areas of the park are made available for tribal cultural and spiritual practices. Lakota artists, historians and performers also share their knowledge and craft regularly with park visitors, he said.

Sometime around the end of the year, a new circular garden will open with native plants and stone spokes aligning with cultural sites throughout the Black Hills, Perez-Foust said. He said it is based on Native stone hoop designs found throughout North America. And the park is producing new interpretative films to be released next summer that will include Indigenous perspectives on Mount Rushmore.

Those are valuable steps. But they won’t go far enough for Tilsen and others who want the land returned. Protests are part of that effort.

Tilsen and NDN Collective organized a road blockade at Mount Rushmore on July 3, 2020, prior to a fireworks display and program headlined by then-President Donald Trump. After an altercation with law enforcement, Tilsen and some of the other protesters were arrested, although their charges were later dropped in an agreement with the prosecution.

That protest at Mount Rushmore was one of many over the years at the memorial, including occupations there by Indigenous protesters in the early 1970s.

“For generations Indian people have been protesting at Mount Rushmore,” Tilsen said.

Those protests will continue, because the issue is far from settled. And Nick Tilsen will continue to speak out in ways that will make old white guys like me uncomfortable.

But if we truly believe in democracy, it’s our job to listen.